"Market Rate" is Code for Maximum Harm

For too long, the world of impact investing has been caught in a financial trap, tethered to an antiquated, extractive benchmark: the market rate. This comfortable fiction has hindered our ability to create genuine change. The only way to break free is to cut the cord and build our own metric for success, one that is durable, resilient, and centered on People, Planet, and Prosperity.

For those of us working to build an economy of well-being, we must be clear: A "market rate return" is simply the highest investor return the current market structure will bear. It is the measure of maximum extraction, inherently reliant on minimizing costs by externalizing harm to the planet, to communities, and to workers. When we demand this rate, we are structurally demanding the maximum amount of violence and harm the system allows us to get away with.

For too long, the nascent world of impact investing has tethered itself to this traditional financial benchmark, a metric that is fundamentally arbitrary, historically blind, and morally inert. This comfortable fiction allows wealth managers to focus on a singular goal of making money for their clients (and themselves) while ignoring the harms created by that investment. It’s time to cut the cord and stop letting the system we are trying to fix define our standard of success.

Sound financial management does not mean enshrined servitude to antiquated, extractive metrics that actively ignore our core mission: to build a world of well-being.

The core problem with centering our thinking on a "market rate" benchmark is that it inherently centers and legitimizes the interests of a single stakeholder: the investor. It demands that every strategic decision, every capital deployment, and every exit timeline be optimized for the growth of a fund's portfolio, leaving the needs of workers, communities, and the planet as secondary concerns, or worse, as externalized costs. If we truly believe in stakeholder capitalism, we must jettison a metric that ensures investor primacy always wins, at the cost of everything else including investor health in the long run.

The Arbitrary Origin Story of Benchmarks

We’ve normalized the idea that the S&P 500, or a private equity Internal Rate of Return (IRR) target, represents some immutable law of economics. They don't: They are constructs.

Early indices like the Dow Jones and the S&P were developed as simple, quantitative tools to gauge industrial health, born from the limited data sets of an industrializing economy and the need for basic comparability. Over time, these basic tools were weaponized, transformed into The Standard, a non-negotiable hurdle for virtually all asset classes.

This fixation quickly spread to private capital. If your venture fund isn't chasing a 20% IRR or hitting "top-quartile" performance in a specific benchmark, you're viewed as conceding return. These targets became the new, equally blind standard, even for capital dedicated to solving the very problems the market created.

This slavish devotion to maximizing the investor's financial outcome permeates every single investment category:

- Public Equities: Managers are judged almost solely against stock market indices like the S&P 500, driving a short-term focus on quarterly earnings and shareholder value above all else.

- Private Equity & Venture Capital: Success is defined by target Internal Rates of Return (IRR) designed to beat peer funds, a measure that pushes managers to slash costs, ignore social debt, and execute rapid, value-extractive exits.

- Private Credit & Debt: Lenders benchmark against risk-adjusted rates, meaning any discount given for achieving positive social outcomes (like lower rates for energy-efficient affordable housing projects) is seen as a "concession" rather than a reduction in long-term systemic risk.

- Real Estate: Performance is typically measured against NCREIF or other property indices, which quantify appreciation and cash flow without measuring displacement, community benefit, or long-term ecological footprint.

In every case, the yardstick is the same: maximum financial return for the capital owner, achieved regardless of the resulting harm.

But what if these revered benchmarks are not just flawed, but demonstrably arbitrary constructs?

The Proof of Arbitrariness

To believe a benchmark represents an objective truth is to willfully ignore financial history. These metrics are subjective selections defined by those who created them, designed for the convenience of one party and easily discarded when they stop serving those in power.

Consider two crucial examples:

- LIBOR’s Demise: For decades, the London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR) was the bedrock for hundreds of trillions of dollars in global debt, loan, and derivative contracts. It was treated as gospel. Yet, it was ultimately exposed as easily manipulated and based on subjective, unaudited bank submissions, leading to its mandatory, permanent phase-out. If a benchmark governing global finance is arbitrary and corruptible, what does that say about the S&P 500 - or any other arbitrary benchmark?

- The Blindness of GDP: Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is arguably the single most important national-level economic benchmark. It was created quickly in the 1930s by economist Simon Kuznets primarily to measure war-making capacity. It never claimed to measure welfare or prosperity. Kuznets himself warned congress against using GDP as a primary metric to measure the wellbeing of a nation. Despite this, GDP has become the de facto global measure of success. The absurdity is clear: GDP goes up when oil spills require massive cleanups, when hospital systems treat pollution-induced disease, or when disaster requires rebuilding. It counts the cost of breaking things as "growth," proving that the core metric driving global economies is utterly blind to human and ecological well-being.

The absurdity and moral bankruptcy of centering our economies on a metric like GDP is a topic that deserves its own deep dive. We’ll explore that further in a future post.

The Fickle, Disposable History of Benchmarks

If these metrics were scientific laws, they would be permanent. Instead, the history of financial benchmarks is littered with discarded, revised, or politically motivated metrics that prove their inherent fallibility:

- The Original Dow Jones's Price-Weighting: The world's oldest index began as a simple, arbitrary average of 12 industrial stocks weighted purely by price, meaning a stock trading at $100 had ten times the influence of a stock trading at $10, regardless of the company's size or actual economic importance. This arbitrary and absurd weighting scheme, flawed from the start, was eventually abandoned for a more robust (but still subjective) methodology.

- The Absurdity of Market Capitalization Weighting: Many of today's most common indices (like the S&P 500) are capitalization-weighted. This means the benchmark's performance is dominated by its largest, most expensive companies. The illogical premise is this: we invest the most in companies only because they are already the most expensive. This creates a self-reinforcing bubble where overvalued assets drive the index up, forcing compliant investors to buy more of the inflated stock simply to match the benchmark, a strategy built on herd mentality, not fundamental value.

- The Rise and Fall of Tobacco/Fossil Fuel Indexes: In the 1990s and 2000s, it was standard practice to include Tobacco, Alcohol, and later Fossil Fuel companies in almost all broad market indices. As ESG and climate activism grew, pressure forced the removal of these sectors from many mainstream and passive funds, a clear admission that their inclusion was morally arbitrary and not economically required. Benchmarks evolve not by scientific discovery, but by social pressure.

- MSCI's China A-Shares Inclusion: For years, MSCI excluded China's domestic A-shares from its global Emerging Markets Index because of concerns over market accessibility and political interference. In 2018, it began a phased inclusion driven by political and investor demand for exposure, injecting hundreds of billions into the market based on a change in arbitrary screening rules, not objective economic necessity.

- Sector Rotations in Private Equity Benchmarks: Which investments qualify for "top-quartile" benchmarking in private markets often shifts dramatically based on transient political winds. A fund praised for maximizing returns in distressed coal assets one decade might pivot to maximizing returns in social impact housing the next, proving that the benchmark's value system is totally fungible and determined by the fashion of extractive opportunity.

When we chase these arbitrary standards, especially in private markets where "top quartile" performance often represents funds optimized purely for financial extraction, we are implicitly agreeing to optimize for the most extractive, highest risk-taking peers, rather than for system resilience or social benefit.

The Moral Myopia of Financial-Only Metrics

The true offense of the market rate benchmark is its stunning moral myopia. Traditional financial metrics are systematically blind to externalities, the positive and negative impacts on people and the planet.

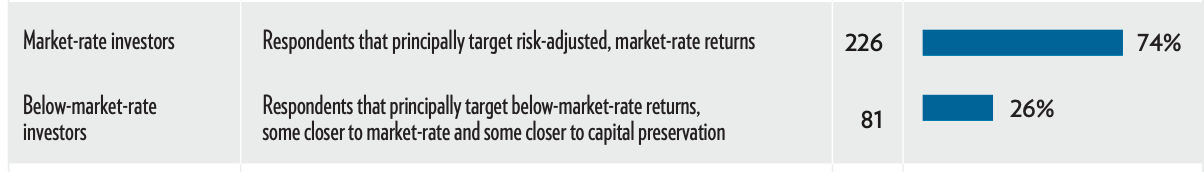

This is a problem that extends even into the world of mission-driven capital. A 2023 survey from the Global Impact Investing Network (GIIN) reveals that 74% of impact investors target market-rate returns versus 26% seeking below-market returns. While the survey tracks investor counts rather than total capital raised by return philosophy, larger investors disproportionately target market rates with 90% of large investors seeking market-rate returns compared to just 60% of small investors suggesting the capital concentration favoring market-rate approaches is even more pronounced.

This is where the stupidity solidifies into something genuinely harmful: by successfully matching market rates, impact investors unknowingly reinforce the structural violence baked into the benchmark itself.

When Market Returns Require Cutting Safety: Norfolk Southern and East Palestine

In the decade before East Palestine, Ohio burned, Wall Street fell in love with a concept called "Precision Scheduled Railroading." PSR, as the industry called it, was beautifully simple: run longer trains with fewer workers, defer maintenance where possible, speed everything up, cut everything you can. The promise? Higher profit margins. Better operating ratios. Market-beating returns.

Norfolk Southern adopted PSR in 2019. Investors celebrated. The company's operating ratio improved from 65.4% in 2018 to 60.4% by 2022, meaning more revenue converted directly to profit. The stock climbed. Executives got bonuses. Everything the market measures said this was working.

What PSR actually meant on the ground:

Trains got longer, sometimes stretching nearly three miles. Crews got smaller. Inspectors had less time to check each car. Maintenance got deferred when it didn't meet cost-benefit thresholds. Safety investments that might prevent disasters but couldn't prove immediate returns got shelved or fought.

The industry knew what this meant. Internal communications and industry studies showed PSR correlated with increased derailments and safety incidents. But the calculus was clear: invest in preventing low-probability disasters, or deliver the returns Wall Street demanded?

The rail companies chose returns. They lobbied aggressively against safety regulations that would cost money: electronically controlled pneumatic brakes (ECP brakes) that could stop trains faster. Requirements for newer, safer tank cars rather than the grandfathered ones. Minimum crew size rules. Two-person crews cost more than one. ECP brakes cost more than older systems.

Every safety improvement had a price tag. Every price tag reduced margins. Every margin reduction disappointed investors. The market didn't just ignore safety concerns. The market actively rewarded companies for deprioritizing them.

Norfolk Southern chose older DOT-111 tank cars for the train that rolled through East Palestine, cars known to puncture easily in derailments. These cars didn't meet newer safety standards, but they were grandfathered in, and replacing them would cost money. The company had lobbied against rules that would have required their phase-out.

Then came February 3, 2023.

Fifty cars jumped the tracks in East Palestine, Ohio. Vinyl chloride, a known carcinogen, spilled into the soil and water. To prevent an explosion, authorities conducted a "controlled release," igniting the chemicals and sending a massive plume of black smoke over the town of 4,700 people.

Residents reported immediate symptoms: burning eyes, rashes, nausea, headaches. Their pets died suddenly. Foxes, chickens, fish floating belly-up in streams. The air smelled like burning plastic for weeks. Children developed nosebleeds. People couldn't sleep, couldn't breathe right, couldn't trust their own homes.

Within days, residents were told it was safe to return. But the fear didn't leave. Property values collapsed. Homes that families had spent decades paying off became unsellable overnight. Small business owners watched their customer base evaporate. A town that had existed for 150 years now carried the stench of contamination, both real and reputational.

Maria, 67, can no longer drink from her well and doesn't trust the bottled water the company provides. The Thompson family's three-generation farm is now "the contaminated property" that no one will buy. Jami Wallace developed a mysterious rash after returning home and now lives in constant fear about what's in her children's bloodstream. A seven-year-old has panic attacks when he hears trains.

And the market's response?

Norfolk Southern's stock dipped briefly, then recovered within weeks. Why? Because from a financial perspective, the disaster was manageable. The company set aside $803 million for costs, a figure that sounds enormous until you realize Norfolk Southern's annual revenue exceeds $12 billion. As a percentage of revenue, East Palestine was a 6.7% hit, a bad quarter, but not a structural problem.

More importantly, the fundamental business model hadn't changed. PSR was still delivering higher margins. The operating ratio was still industry-leading. The cost cuts that made the derailment more likely were still boosting returns. Financial analysts noted the company's "strong fundamentals." Credit ratings held steady. By year's end, the stock had fully recovered.

The system worked exactly as designed.

Market-rate return expectations pressured Norfolk Southern to maximize margins. Maximizing margins meant adopting PSR. PSR meant cutting costs everywhere possible, including safety. Cutting safety costs made derailments more likely. When the predictable disaster struck, insurance absorbed most costs, the company contained liability, and the stock recovered.

The financial benchmark said: "Crisis managed. Returns protected. Well done."

This is not a story about one negligent company. This is how the system allocates risk.

Every railroad faces the same return expectations. Every railroad adopted some version of PSR. Every railroad made similar calculations: invest in safety equipment that might prevent disasters, or deliver the margins investors demand? The market punished companies with higher operating ratios (more costs, including safety costs) and rewarded companies with lower ones (fewer costs, including fewer safety investments).

The choice was structural: meet market-rate returns by optimizing costs and externalizing risk, or accept below-market returns by internalizing safety costs. You cannot simultaneously maximize returns and maximize safety when safety is expensive and disasters are infrequent enough to insure against.

Norfolk Southern made the rational choice within a system that measured success by profit margins and stock price. They cut costs to boost returns. They fought safety regulations that would reduce margins. They used older tank cars because replacing them costs money. They ran longer trains with smaller crews because efficiency drives returns.

East Palestine was the cost of that optimization. But East Palestine doesn't show up in the operating ratio. The destroyed community, the poisoned water, the children with nosebleeds, the family farms now worthless—these are externalities. Costs borne by people with no shares, no votes, no voice in the calculation.

When we demand that impact investments achieve market-rate returns, we are demanding they make the same calculation Norfolk Southern made.

We are saying: optimize for the metric that rewarded cost-cutting over safety. Compete against companies that externalize harm to boost margins. Hit the same return targets as firms that chose profits over people because the benchmark cannot tell the difference.

The financial statements said Norfolk Southern was efficient, competitive, and resilient. Ask East Palestine about resilience. Ask them about the market-rate returns built on their poisoned water.

The benchmark doesn't measure what you had to cut to achieve the return. It doesn't measure whose safety you traded for whose profit. It doesn't measure the seven-year-old's panic attacks or Maria's contaminated well.

It only measures the return. And by that measure, Norfolk Southern succeeded.

A New Framework: People, Planet, Prosperity (PPP)

For those of us committed to impact, the benchmark should not be an external, irrelevant index of extraction, but a bespoke, mission-aligned framework built on three non-negotiable pillars.

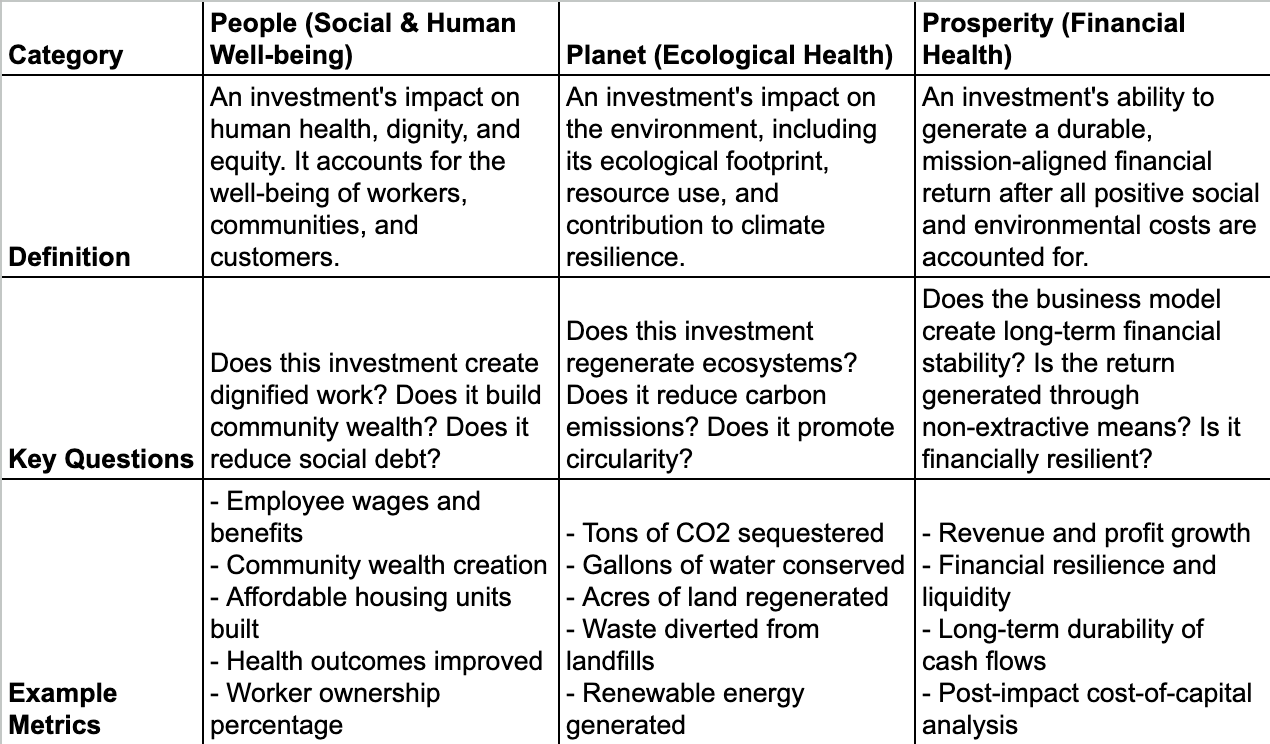

We propose shifting the focus to a People, Planet, Prosperity (PPP) framework. This framework requires that an investment be deemed successful only if it achieves targets across all three dimensions, thereby forcing the creation of durable, resilient value.

The PPP Framework demands a three-bucket approach:

By redefining Prosperity to require sustainable financial health after the costs of positive and negative impact are accounted for, we invert the destructive logic of the old system. We demand that returns be generated through resilience, not through extraction.

The Opportunity Cost of Compliance

The greatest cost of chasing market rates isn't financial: it's the massive opportunity cost of the transformative investments we dismiss.

Investments that genuinely de-risk a community, build resilient systems, or pilot radical new solutions often require "catalytic" or "patient" capital. This capital must inherently reject the arbitrary IRR targets and rigid exit timelines defined by conventional private markets.

When we cling to the illusion that we can solve the world's most complex problems while still hitting a top-quartile 20% IRR, we actively dismiss the best and most durable solutions. The investment that can save a community from displacement, build permanent affordable housing, or transition a business to true employee ownership rarely adheres to the timelines and return profiles of an extractive market.

Defining Our Own Success

We are impact investors. Our purpose is to fix what the market has broken and build what the market ignores. We must stop letting the perpetuators of the old system define the goalposts of our success.

The frameworks for change exist. The models, from cooperative trusts to Doughnut Economics, are being built. What is missing is the collective courage from capital owners to sever the toxic relationship with arbitrary market benchmarks.

Let's commit to defining our own selective truth, one that selects for positive externalities, structural equity, and enduring systems change. The future of true impact rests on this intellectual independence.

The Moral Imperative of the Question

The next time you or someone on your team prepares to evaluate a deal by asking, “Is this market rate?”, stop. Feel the full weight of what you are actually asking.

That question is not a request for neutral data. It is a request for maximum permissible extraction.

It is asking, “What's the maximum extraction?” It is asking, “How many jobs can we cut? How low can we pay our workers? How much pollution can we release without getting fined? How much can we spend lobbying to avoid regulation and taxes? What’s the fastest we can flip this asset and cash out, and what's the minimum we have to invest to do it?”

It is asking, “How much violence to people and planet are we required to ignore to maximize the financial return of this portfolio?”

To purge this toxic logic from our organizations, we must substitute that old question with the new moral imperative: "Does this investment generate Prosperity after accounting for the costs to People and Planet?"

The choice is clear. We must stop chasing the ghost of market returns and start building our own measures of success. What will your People, Planet, Prosperity (PPP) benchmark be?

Member discussion